While discussing this book with my dad at lunch on Sunday, the subject of Wikipedia came up. Not surprising, since Shirky uses it as a prevalent example of the possibilities of organizing people over the Internet. My dad, of course, is one of the Wikipedia nay-sayers, who is convinced that something that can be edited by anybody can not be relied on to be correct in any way. He pointed to the article on Barack Obama, which months before the election already said that he was the 44th president of the United States. This may have been true, but if he had check in the next day, the incorrect information would probably have already been fixed. My dad would have probably preferred the failed Nupedia, which relied on academic experts donating their time to create articles which were highly regulated and had to go through several approval levels before being published (p.111). Although, had the website survived, these articles would have been more academically accepted, there would have been much fewer of them, and they would never be as up to date as the existing Wikipedia, which can be updated as events are happening.

The amazing thing about Wikipedia and other sites like it is not just that it exists, but that it functions, and functions well. The fact that people are willing to come together and work on an encyclopedia for free, and that it is actually correct most of the time is the truly amazing thing. Or is it? According the Shirky, this type of behavior is popping up all over the net. From collaborative programmers creating Linux to long lost friends finding each-other and planning reunions, people who may have never worked together are now cooperating to create things.

The reason people are doing this (get ready for an Economics word) is because the transaction cost has been greatly lowered (p.47). Things that used to be so prohibitively expensive or inconvenient that they were barely, if ever, considered possible are now as simple as a click of a button.

Prior to the Internet, especially Facebook, I probably would have never stayed in contact with many (if any) high school or college friends. Now, I know what they are up to, and can share in their life changes (so many babies!!) and coordinate meeting up with them when they are in town with nearly effortless ease. My 5 year college reunion is coming up in a few weeks, and although I'm excited about seeing everyone, I kind of already know what's going on in their lives. What I'm really exited to do, is to finally meet all of those husbands and babies I've seen pictures of and to see Kelly's new hair cut in real life. No matter that I have not seen or technically talked to most of these people since graduation, I still feel like I am part of their lives. Because of this type of connection, a group of my friends have been able to coordinate an informal reunion during the official reunion weekend.

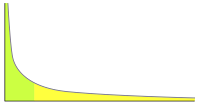

Of course, as Shirky points out, participation in this coordination is not in any way equal. There are 1 or 2 people who have been doing the majority of the discussion and preparation on the email list, while the majority of people have only stated whether or not they will be able to attend. This is what Shirky refers to (Economic word again) as the power law distribution. " A power law describes data in which the nth position has 1/nth of the first position's rank (p.125)," and it seems to be in effect for any participation/coordination/creation that goes on on the web. For example, the vast majority of Wikipedia users end their participation at that; using. A small percentage of users do end up for one reason or another) becoming contributors. The vast majority of these contributors end up (like myself) only making one edit to one article. A small percentage of those contributors make more than one edit, and as the amount of edits goes up, the amount of contributors making those edits goes down exponentially, resulting in a fraction of a percentage of people being responsible for the vast majority of the work.

This is also referred to as the 80/20 rule, meaning that 20% of the participants count for 80% of the work. This statistic would never fly in the corporate (or any paying) world, but it works on the web, because the transaction cost is so low. People are working for free, because they want to. And other people's work, or lack of work is not taking away from the work that they have done. The ones doing the most work (like the people organizing our informal reunion) are the ones who care the most, and the ones who participate the least are the ones that have the least time/interest, but still want to be a part. Shirky contends that social media provides for both types of users, and everyone in between, thus creating a place where everyone can participate in the way that they are most willing/able, and in doing so, they can create things/possibilities that were never before conceivable.

Wikipedia works against all odds, because people care enough to make sure that it does. The same thing applies to any of thousands (or maybe millions) of other collaborative Internet sites, because of love. Not the squishy kind of love, but the passionate kind of love. Social media opens up doors to success (and even more failure) that allow people to explore and pursue their passions in ways they have not been able to do before. What doors has it opened for you?